Less than 90 minutes before the documentary film “Fog of Srbrenica” was set to play at the 2017 ACT Human Rights Film Festival, Serbian filmmaker Samir Mehanovic’s cell phone rang.

Mehanovic, who has the physique of a former Olympic weightlifter, was casually walking the few blocks from The Armstrong Hotel to the afternoon screening at the Lincoln Center’s Magnolia Theatre. He kindly answered the phone, then came to an abrupt stop.

The look on his face instantly changed before he spit out, “What?”

“The region code on the player and DVD is incompatible,” said Kristy King, festival director of operations at the time. “Their DVD can only play region 1 media.”

Mehanovic’s disc was set for region 2, which comprises Europe, Japan, the Middle East, Egypt, South Africa, and Greenland.

Mehanovic, clearly irked, thought for a while and then told King they’d have to go with a back-up streaming option. The quality of the film would suffer, he said, but at least the show could go on. So be it. He resumed walking.

A minute later his phone rang again. Another option had emerged. Professor Scott Diffrient, festival director of programming and film studies scholar, happened to have a couple of region-free DVD players at home, along with a multi-region player that goes between regions 1, 2 and 3. He was heading home to retrieve the machines and would hopefully return with just enough time to test-run the disc.

Welcome to regional lockout.

Analog Logic in a Digital World

“Historically, media industries have divided global content markets geographically for a combination of logistical, cultural-linguistic, and economic reasons,” writes Communication Studies Assistant Professor Evan Elkins in his forthcoming book, Locked Out.

Elkins specializes in digital media industries and technologies, globalization, access, and cultural difference. And he says that by splitting the world into territories corresponding with national and regional borders (there are six) and treating each territory as a market, media industries can alter prices, stagger release dates, and distribute different versions of a product to different places.

Regional lockout is a mechanism of technological control that emerged following the advent of digital software and networking technologies that made it easy (and illegal) to copy and share media. In the digital media space, regional lockout occurs primarily through two methods of DRM —region codes in DVDs and video game consoles and on-demand geoblocking through IP detection software—that persist through a private regulatory sphere of influence.

“There’s nothing that legally binds DVD manufacturers to include the region code system on discs,” Elkins says. “They could manufacture without it, but then Hollywood studios would not license content to them.”

Fear of exclusion in a global media market is real. As a result, regional lockout through DRM persists, although does not go unchallenged, and, Elkins argues in Locked Out, creates a “fulcrum of geocultural discrimination that divvies up media access along lines of privilege and power,” where distribution companies and streaming platforms (predominantly American) decide which countries get to see which content and when.

“Media distribution has historically corresponded with social status and discrimination,” Elkins says.

Hu(lu) stole our global village?

Elkins says this promise was fiercely challenged during the 1990s dotcom boom by cultural critics who argued that Silicon Valley married the liberal vision of personal freedom via the internet with a profit-driven motive that was dependent on free and low-paid wage labor. Labor that came from both users (free labor) and workers (low-wage outsourced labor) in the tech industry who do coding, design, and content moderation.

“With Locked Out, I argue that global media companies have exceled at promoting their own vision of a commercialized global village, yet their distribution practices and uses of technology have stifled global interconnection,” Elkins says.

Elkins sees that certain elements of the global village are theoretically possible, in that the technological infrastructure exists to connect many around the world. But, when it comes to anyone being able to access whatever digital media they want? Well, that’s a different story.

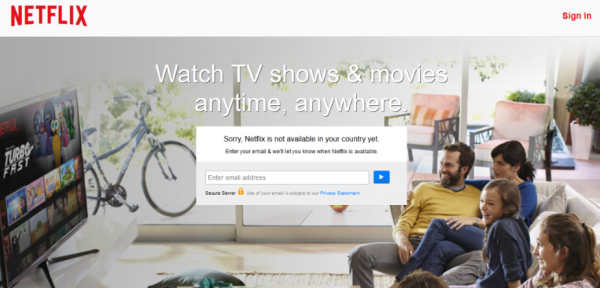

If you’ve ever traveled to another country and tried to log in to your Netflix account, you have most likely been a recipient of this message:

“Increasingly around the world, more and more people are accessing forms of culture, social networking, and communication through a smaller and smaller number of (mostly American) platforms,” Elkins says.

Internet users the world over are routinely blocked from visiting streaming platforms (yes, there are a few workarounds). To counteract consumer criticism, Netflix and Amazon have expanded streaming capabilities to many countries. Yet, in these places they employ a different form of control by adopting a new flavor of DRM. Instead of blocking content altogether, they reduce or completely remove third party content, and stream only their original content.

The Diasporic Workaround

“A lot of people in the United States think of the DVD as an obsolete or dead technology,” Elkins says. “But look around the world. That’s not the case at all. Very robust DVD-sharing economies exist.”

This type of pirate media economy is gaining interest from media studies scholars, says Elkins. “A lot of these scholars are noting that informal media trade, or piracy, is probably more of the global norm than formal media trade,” he says.

Perhaps this pirate DVD economy is having a noticeable effect on media giants’ bottom lines. Whether through illegal or legal mechanisms, Elkins says that more and more streaming platforms are trying to cater to immigrant communities by making more international content available. He specifically points to irokotv.com, founded by a London-based Nigerian who wanted to make Nollywood (the Nigerian film industry) movies available to the African diaspora living in the UK.

Fixing Regional Lockout

Despite rhetoric from some streaming platforms that they would drop all of their regional geoblocks (Netflix in particular announced this), Elkins says this is inaccurate. China has not let entertainment markets pierce its consumer bubble and the streaming platform is also unavailable in Crimea, North Korea, and Syria due to sanctions.

Furthermore, a variety of regional “hiccups” prevent a completely abolished geoblocked world from occurring. Elkins points to poor infrastructure, national content regulations, variable pricing in different territories, and digital entertainment companies’ hesitance to expand into new markets too quickly. In fact, “most major digital entertainment platforms still have some kind of geoblock in place, or at least their prices and content libraries vary from nation to nation,” Elkins says.

As much as streaming platforms would like us to believe otherwise, Elkins reminds us that the internet was never one globally uniform medium. “It is, in many ways, a global infrastructure, but on top of that infrastructure exist different ‘internets’ of varying quality and levels of access,” he says. “It was always globally diverse and disjunctive.” And will likely continue to be so.

– Written by Carol Busch