November 12, 2020 – Article by Karrin Vasby Anderson in The Conversation.

Shortly after news networks called the presidential race in favor of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, Harris’ husband, Doug Emhoff, posted the following tweet:

More than a heartwarming glimpse into the vice president-elect’s private life, the tweet signaled that gender norms in a Biden/Harris administration will differ from those on display in the White House during the past four years.

In fact, a number of tweets went viral over the weekend of Nov. 7 and 8 that showcased a version of masculinity that contrasts sharply with the one projected by Donald Trump.

As a communication scholar who studies gender and political leadership, I’ve written about how gender stereotypes collide with our culture’s understanding of the U.S. presidency, casting presidents as the patriarch in chief and inhibiting women’s campaigns for the top job.

These stereotypes also constrain the men who have served as U.S. president, often promoting a “toxic” version of masculinity that Trump took to an extreme.

The 2020 campaign gave voters an opportunity to compare and contrast how the two campaigns modeled gender roles differently. These differences not only reveal important insights about each campaign; they also shape the roles of “president” and “vice president,” making it more or less likely that, in the future, those offices can be held by someone other than a heterosexual white man.

Different approaches to masculine leadership

The phrase “toxic masculinity” is often misunderstood. “Toxic masculinity” does not mean that men are bad or that every version of masculinity is “toxic.”

It means that a particular version of masculinity – one that discourages empathy, expresses strength through dominance, normalizes violence against women and associates leadership with white patriarchy – is bad for people of all genders and for society more generally.

Trump’s propensity to resist empathy, insult women and project dominance is well documented. The onset of COVID-19 offered a particularly sharp distinction between Trump’s and Biden’s leadership styles.

Writing for The Washington Post, Matt Viser observed that Biden’s and Trump’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic reflect very different approaches to masculinity. Trump mocks Biden’s mask-wearing and flaunts his recovery from the virus as a sign of strength and manliness. Biden derides Trump’s unwillingness to wear a mask as a silly “macho thing” and urges supporters to “take care of your neighbors” by masking up.

In the context of a global pandemic, these distinct leadership styles have life-and-death consequences. To appreciate how far-reaching the implications are, however, consider a few more snapshots from the 2020 campaign.

In the campaign’s final days, former White House videographer Arun Chaudhary tweeted a 2018 clip of Biden hugging and comforting the disabled son of Chris Hixon, the heroic teacher who died trying to save students during the mass shooting on Feb. 14, 2018, at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School:

The tweet went viral, indicating many people’s receptiveness to a more humane version of masculinity.

The Biden/Harris victory seemed to open space for other men to similarly reject the emotional strictures of toxic masculinity. Appearing on CNN, commentator Van Jones was overcome with emotion when reflecting on the impact of the election. He connected his feelings explicitly to the cultural construction of masculinity, saying, “Being a good man matters. I just want my sons to look at this …”

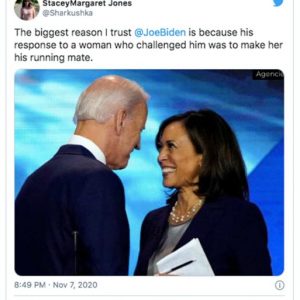

Moreover, although Trump often asserts himself by making up derogatory names for women who challenge him, Twitter user StaceyMargaret Jones made clear that she views being respectful to assertive women as a sign of strength:

Expanding views of gender

In addition to perpetuating sexism, toxic masculinity is associated with homophobia and transphobia, fueling violent attacks on trans women, particularly trans women of color.

Trump’s transphobia took the form of his policy aimed at banning transgender individuals from military service, a policy he impulsively announced via tweet on July 26, 2017, catching the Department of Defense off guard.

That’s why a small but groundbreaking moment from Biden’s victory speech was so important to the LGBTQ community. Biden identified transgender people as an important part of his electoral coalition, demonstrating a very different approach to gender identity than that of President Trump.

Tweets from the transgender community confirmed the significance of a U.S. president-elect acknowledging voters who challenge traditional gender norms, as did the cheers that erupted from patrons at a Philadelphia bar during the speech:

LGBTQ activist Charlotte Clymer argued in mid-October that Biden’s support of LGBTQ human rights is more than lip service, and Biden is on record identifying discrimination against transgender people as the “civil rights issue of our time.”

Biden’s and Harris’ approaches to gender roles in their personal lives also will expand what the president and vice president symbolize.

Communication scholars have documented the ways in which the U.S. presidency historically has been a “two-person career” in which the president’s family is supposed to represent an idealized version of the traditional American family, with the president/father as the head, the wife/first lady in a supporting role, and obedient children rounding out the picture. The ceremonial duties required of the president and first lady typically have required even career-focused political spouses to put their work on hold during their time in the White House.

Jill Biden, however, might be the first presidential spouse to continue to work in her chosen profession – teaching at a community college – while serving as first lady. And Doug Emhoff will be the first male spouse of a woman vice president, causing sometimes humorous confusion over what he should be called: second gentleman? second husband? vice dude?

The serious point to be made is that the small ways that Jill Biden and Doug Emhoff will broaden our expectations of presidential and vice presidential spouses also expand the possibilities for who can run for the top jobs.

So, even though the 2020 presidential campaign pitted two white, heterosexual men against each other, the election of Biden and Harris poses a challenge to how we envision the president and vice president.

American masculinity has been subjected to well-deserved critique, and the negative effects of toxic masculinity are manifold and substantial. But the photos tweeted in recent weeks – of men hugging others with compassion, crying openly and acknowledging women and the LGBTQ community with respect and gratitude – remind us of one thing: This, too, is American masculinity.